Following Moore's Law, the continuous shrinking of transistor size in integrated circuits—the number of transistors on a microchip roughly doubling every two years—is a remarkable engineering feat that pushes the limits of fundamental physics. Transistors are key components that regulate the current between terminals (conductive junctions) by switching current on and off. As transistor size decreases, switching speeds increase, enabling integrated circuits to process information much faster.

However, as transistor sizes shrink to the nanometer scale, interconnects—the metal wires connecting transistors to other circuit elements on a microchip—have become a major bottleneck for processing speed. Therefore, improving the performance of integrated circuits in next-generation electronic devices cannot rely solely on shrinking transistor size; it also requires the development of novel interconnect materials.

What is interconnect?

Interconnects are used to transmit signals from one circuit element to another. The time it takes for a signal to travel through a wire is called the resistance-capacitance (RC) time delay, which depends on the inherent resistance of the interconnect material and the capacitance of the surrounding dielectric element (an electrically insulating material that can be polarized by an electric field). Therefore, copper, as one of the most conductive metals, has long been the standard material for interconnects. However, simulation results show that the RC time delay of the smallest interconnect currently in use (approximately 15 nm wide) can be up to 20 times faster than the switching speed of a transistor.

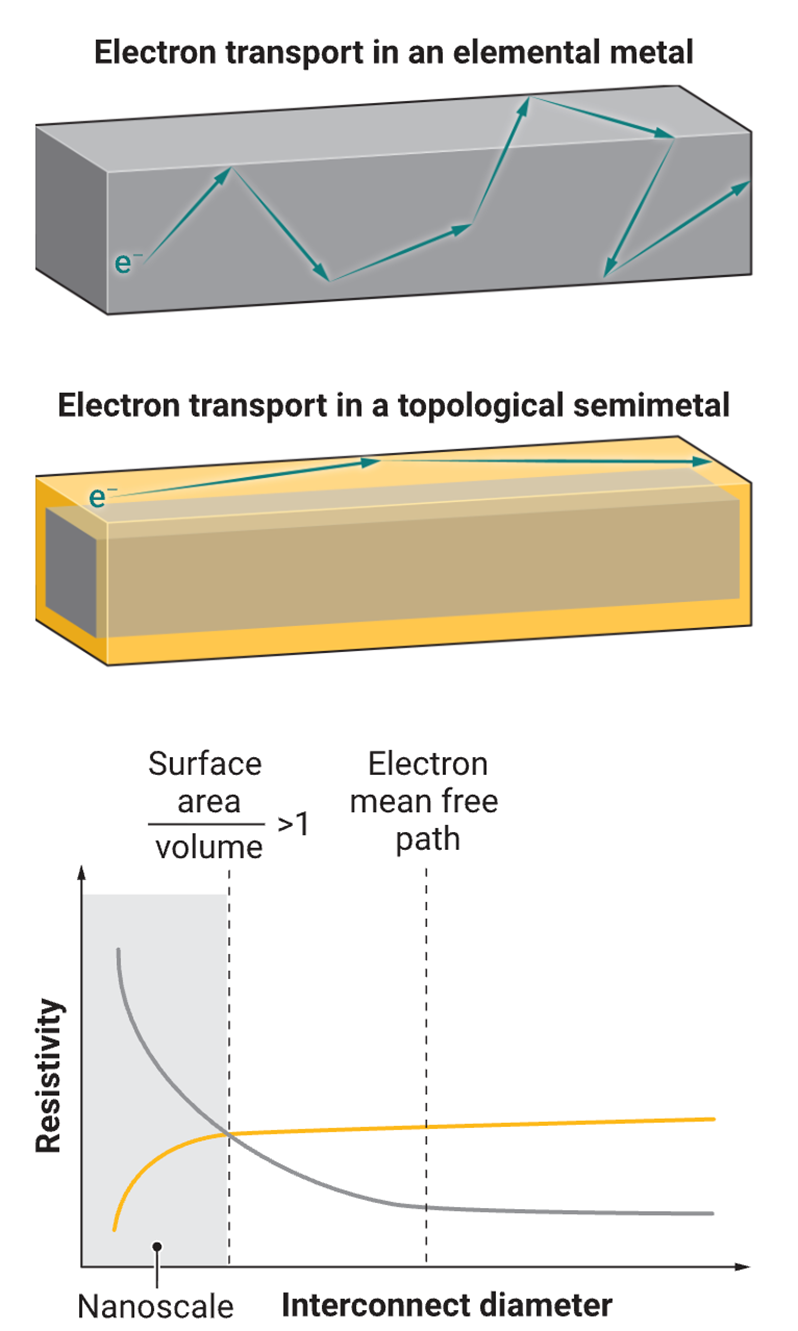

Why is the RC time delay of interconnects so large? The resistance of copper increases as its size decreases. The movement of electrons within the metal is the fundamental reason for this size effect on resistivity. The electron mean free path (λ) refers to the average distance an electron travels within a material. Beyond this distance, electrons are scattered by the thermal vibrations of the ordered three-dimensional atomic arrangement in the crystal lattice. When the size of the interconnect approaches the electron mean free path of the material, additional scattering occurs, primarily at grain boundaries (the interfaces where crystals with different orientations meet) and surfaces. This results in the resistivity of the interconnect being significantly higher than the inherent resistivity of the material.

For example, when the width of a copper wire is smaller than the mean free path of electrons in copper (40 nm at room temperature), it leads to increased electron scattering, increased resistance, and thus a longer RC time delay (see figure). Although solving this problem seems daunting, it is not without precedent. Computer chips prior to 1997 used aluminum interconnects, but these were later replaced by copper interconnects due to the inherent high resistivity of aluminum and the voids created by electromigration (atomic movement caused by high current) in the material.

The mean free path of electrons is less than that of copper

The semiconductor industry has turned its attention to alternative materials with a shorter mean free path (MFS) than copper, such as ruthenium (λ = 6.6 nm). Optimizing deposition processes, padding layers (thin layers adjacent to copper that promote adhesion and prevent diffusion), and microchip design will allow ruthenium to undergo several rounds of size reduction before interconnect dimensions approach its MFS. Therefore, finding compounds whose resistivity variations differ from those of elemental metals is a necessary approach to solving this long-standing problem.

Topological semimetals are a promising class of materials, representing quantum phases of matter with topologically protected electronic states. These compounds possess unique electronic band structures (the allowable range of electronic energy levels related to electronic momentum), which can significantly alter electron transport behavior in solids. Some topological semimetals, such as Weyl semimetals and chiral semimetals, exhibit unique surface electronic states called surface Fermi arcs. These surface Fermi arcs are robust to disorder and determine conductivity.

These surface Fermi arcs do not exist in conventional metals such as copper. Unlike elemental metallic interconnects, surface Fermi arcs exhibit reduced resistivity as material size decreases. Furthermore, theoretical predictions indicate zero or extremely low surface scattering during electron movement within surface Fermi arcs, suggesting enhanced conductivity even at small dimensions. Computational studies predict that over 50% of known crystalline compounds should be topological compounds, providing a vast material design space for interconnect applications.

Compounds such as niobium arsenide, niobium phosphide, molybdenum phosphide, and monosiliconized cobalt have been considered potential topological half-metals for interconnects. Among these, niobium arsenide is the most promising candidate. At room temperature, when formed into 200 nm thick strips, its resistivity is approximately 1 to 3 microhm·cm. This is an order of magnitude lower than the intrinsic resistivity of single-crystal (continuous, grain boundary-free lattice) niobium arsenide and close to the intrinsic resistivity of single-crystal copper (1.68 microhm·cm). Moreover, the resistivity of 1.5 nm thick nanocrystalline (solid composed of nanoscale grains) niobium phosphide films is also lower than their intrinsic resistivity.

Furthermore, the resistivity of molybdenum phosphide polycrystalline nanowires (a type of solid with multiple different orientations of grains) is size-independent and comparable to that of copper interconnects with widths less than 25 nm. Due to the absence of grain boundaries that scatter electrons, the resistivity of single-crystal molybdenum phosphide nanowires may even be lower than that of their polycrystalline counterparts.

Single cobalt silicide nanowires

The resistivity of single cobalt silicide nanowires is about 80% lower than their inherent value. Although the line resistance (resistance per unit length) of interconnects is a better indicator of circuit performance than resistivity, these studies provide a comprehensive example of how the resistivity of topological half-metals decreases with size, unlike the case of copper. In fact, at similar interconnect widths, the line resistance of molybdenum phosphide is comparable to that of copper and ruthenium. However, the line resistance of topological semimetals requires further evaluation to accurately predict their performance in integrated circuits.

Research on topological semimetals for interconnects is still in its early stages.

Besides the compounds mentioned above, there are 5 to 10 other topological semimetals with similar properties, crystal structures, and chemical compositions (e.g., tantalum arsenide, tantalum phosphide, and rhodium silicide), but their size-dependent resistivity remains unclear. Studying these materials, especially those with diameters less than 40 nm, will help to better understand resistivity and material stability at the nanoscale. Furthermore, experimental studies of electron transport behavior in topological semimetals are crucial for determining the stability of surface Fermi arcs in the presence of structural disorder, impurities (dopants), and grain boundaries that may occur during fabrication.

For example, computational studies show that the stability of Fermi arcs in Weyl semimetals such as niobium arsenide, niobium phosphide, and tantalum arsenide decreases after the introduction of structural defects compared to chiral topological semimetals such as monocobalt silicide. When the material size is smaller than the critical size (<5 nm), the stability of the Fermi arcs decreases. At thicknesses of several nm, topologically protected surface states can be compromised by wavefunction hybridization (overlap and resulting electronic interactions) from opposite material surfaces. However, theoretical calculations predict that this problem only arises when the material thickness reaches several angstroms, a prediction supported by experimental studies on 1.5 nm thick niobium phosphide films.

Currently, a large number of different types of materials with topologically protected surface Fermi arcs have not been discovered. For example, Weyl topological half-metals and chiral topological half-metals require computationally intensive band structure calculations to accurately characterize the surface Fermi arcs. Ideally, topological half-metals should have a high density of long Fermi arcs on multiple crystal surfaces near the Fermi level (the highest energy level occupied by electrons in equilibrium). Furthermore, properties relevant to practical application conditions, such as oxidation resistance, low-cost elements, and chemical stability with surrounding dielectric materials, should be considered. Extending computational predictions to ternary compounds also helps increase the number of candidate materials to be explored.

High-throughput methods

High-throughput methods can accelerate the experimental screening of potential materials at technology-relevant length scales and morphologies. Combinatorial multi-element thin-film deposition can prepare binary or ternary compounds with different elemental compositions in a sample, and resistivity measurements can rapidly screen the feasibility of each compound as an interconnect material. Low resistivity in a compound in a thin film (two-dimensional) is a strong indicator of its low resistivity in a wire (one-dimensional).

However, good resistivity observed in a thin film does not guarantee the same resistivity in an interconnect material. Therefore, material screening for nanoscale one-dimensional morphologies must be experimentally validated. Nevertheless, existing synthetic methods, such as chemical vapor deposition and gas-liquid-solid growth, require extensive optimization for each compound and are limited to certain chemical systems and sample sizes. Advanced methods, such as thermomechanical nanoforming, which press polycrystalline raw materials into nanostructure molds to extrude single-crystal nanowires of desired diameter and composition, can accelerate the screening of interconnect materials.

Translating laboratory-scale measurements into large-scale industrial production requires a deep understanding of material properties (not just transport behavior). Furthermore, electromigration must be suppressed to prevent interconnect failure. Whether electromigration in topological materials differs from that in elemental metals remains unclear. Furthermore, fabricating topological half-metals under traditional semiconductor foundry conditions is another pressing challenge.

For example, copper interconnects are typically fabricated using electrodeposition processes, but these processes are not suitable for preparing binary or ternary compounds such as topological half-metals. Determining which compounds can be used to fabricate interconnects using conventional techniques such as chemical vapor deposition, physical vapor deposition, and atomic layer deposition will facilitate foundry integration.

Source: Semiconductor Industry Observer